START OF EDUCATION IN THE WORLD THROUGH ISLAM

From the very earliest days of Islam, the issue of education has been at the forefront at the minds of the Muslims. The very first word of the Quran that was revealed to Prophet Muhammad ﷺ was, in fact, “Read”. Prophet Muhammad ﷺ once stated that “Seeking knowledge is mandatory for all Muslims.” With such a direct command to go out and seek knowledge, Muslims have placed huge emphasis on the educational system in order to fulfill this obligation placed on them by the Prophet ﷺ.

Throughout Islamic history, education was a point of pride and a field Muslims have always excelled in. Muslims built great libraries and learning centers in places such as Baghdad, Cordoba, and Cairo. They established the first primary schools for children and universities for continuing education. They advanced sciences by incredible leaps and bounds through such institutions, leading up to today’s modern world.

Interest Towards Education

Today, education of children is not limited to the information and facts they are expected to learn. Rather, educators take into account the emotional, social, and physical well-being of the student in addition to the information they must master. Medieval Islamic education was no different. The 12th century Syrian physician al-Shayzari wrote extensively about the treatment of students. He noted that they should not be treated harshly, nor made to do busy work that doesn’t benefit them at all. The great Islamic scholar al-Ghazali also noted that “prevention of the child from playing games and constant insistence on learning deadens his heart, blunts his sharpness of wit and burdens his life. Thus, he looks for a ruse to escape his studies altogether.” Instead, he believed that educating students should be mixed with fun activities such as puppet theater, sports, and playing with toy animals.

The First Education

Ibn Khaldun states in his Muqaddimah, “It should be known that instructing children in the Qur’an is a symbol of Islam. Muslims have, and practice, such instruction in all their cities, because it imbues hearts with a firm belief (in Islam) and its articles of faith, which are (derived) from the verses of the Qur’an and certain Prophetic traditions.”

The very first educational institutions of the Islamic world were quite informal. Mosques were used as a meeting place where people can gather around a learned scholar, attend his lectures, read books with him/her, and gain knowledge. Some of the greatest scholars of Islam learned in such a way, and taught their students this way as well. All four founders of the Muslim schools of law – Imams Abu Hanifa, Malik, Shafi’i, and Ibn Hanbal – gained their immense knowledge by sitting in gatherings with other scholars (usually in the mosques) to discuss and learn Islamic law.

Some schools throughout the Muslim world continue this tradition of informal education. At the three holiest sites of Islam – the Haram in Makkah, Masjid al-Nabawi in Madinah, and Masjid al-Aqsa in Jerusalem – scholars regularly sit and give lectures in the mosque that are open to anyone who would like to join and benefit from their knowledge. However, as time went on, Muslims began to build formal institutions dedicated to education.

From Primary to Higher Education

Dating back to at least the 900s, young students were educated in a primary school called a maktab. Commonly, maktabs were attached to a mosque, where the resident scholars and imams would hold classes for children. These classes would cover topics such as basic Arabic reading and writing, arithmetic, and Islamic laws. Most of the local population was educated by such primary schools throughout their childhood. After completing the curriculum of the maktab, students could go on to their adult life and find an occupation, or move on to higher education in a madrasa, the Arabic world for “school”.

Madrasas were usually attached to a large mosque. Examples include al-Azhar University in Cairo, Egypt (founded in 970) and al-Karaouine in Fes, Morocco (founded in 859). Later, numerous madrasas were established across the Muslim world by the great Seljuk vizier, Nizam al-Mulk. At a madrasa, students would be educated further in religious sciences, Arabic, and secular studies such as medicine, mathematics, astronomy, history, and geography, among many other topics. In the 1100s, there were 75 madrasas in Cairo, 51 in Damascus, and 44 in Aleppo. There were hundreds more in Muslim Spain at this time as well.

These madrasas can be considered the first modern universities. They had separate faculties for different subjects, with resident scholars that had expertise in their fields. Students would pick a concentration of study and spend a number of years studying under numerous professors. Ibn Khaldun notes that in Morocco at his time, the madrasas had a curriculum which spanned sixteen years. He argues that this is the “shortest [amount of time] in which a student can obtain the scientific habit he desires, or can realize that he will never be able to obtain it.”

When a student completed their course of study, they would be granted an ijaza, or a license certifying that they have completed that program and are qualified to teach it as well. Ijazas could be given by an individual teacher who can personally attest to his/her student’s knowledge, or by an institution such as a madrasa, in recognition of a student finishing their course of study. Ijazas today can be most closely compared to diplomas granted from higher educational institutions.

Education and Women

Throughout Islamic history, educating women has been a high priority. Women were not seen as incapable of attaining knowledge nor of being able to teach others themselves. The precedent for this was set with Prophet Muhammad’s own wife, Aisha, who was one of the leading scholars of her time and was known as a teacher of many people in Madinah after the Prophet’s ﷺ death.

Later Islamic history also shows the influence of women. Women throughout the Muslim world were able to attend lectures in mosques, attend madrasas, and in many cases were teachers themselves. For example, the 12th century scholar Ibn ‘Asakir (most famous for his book on the history of Damascus, Tarikh Dimashq) traveled extensively in the search for knowledge and studied under 80 different female teachers.

Women also played a major role as supporters of education:

- The first formal madrasa of the Muslim world, the University of al-Karaouine in Fes was established in 859 by a wealthy merchant by the name of Fatima al-Fihri.

- The Abbasid caliph Harun al-Rashid’s wife, Zubayda, personally funded many construction projects for mosques, roads, and wells in the Hijaz, which greatly benefit the many students that traveled through these areas.

- The wife of Ottoman Sultan Suleyman, Hurrem Sultan, endowned numerous madrasas, in addition to other charitable works such as hospitals, public baths, and soup kitchens.

- During the Ayyubid period of Damascus (1174 to 1260) 26 religious endownments (including madrasas, mosques, and religious monuments) were built by women.

Unlike Europe during the Middle Ages (and even up until the 1800s and 1900s), women played a major role in Islamic education in the past 1400 years. Rather than being seen as second-class citizens, women played an active role in public life, particularly in the field of education.

Modern Education

The tradition of madrasas and other classical forms of Islamic education continues until today, although in a much more diminshed form. The defining factor for this was the encroachment of European powers on Muslim lands throughout the 1800s. In the Ottoman Empire, for example, French secularist advisors to the sultans advocated a complete reform of the educational system to remove religion from the curriculum and only teach secular sciences. Public schools thus began to teach a European curriculum based on European books in place of the traditional fields of knowledge that had been taught for hundreds of years. Although Islamic madrasas continued to exist, without government support they lost much of their relevance in the modern Muslim world.

|

| Jameah Darul Uloom |

|

| Al Azhar University |

Despite the new systems in place in much of the Muslimworld, traditional education still survives. Universities such as al-Azhar, al-Karaouine, and Darul Uloom in Deoband, India continue to offer traditional curricula that bring together Islamic and secular sciences. Such an intellectual tradition rooted in the great institutions of the past that produced some of the greatest scholars of Islamic history and continues to spread the message and knowledge of Islam to the masses.

#JUST BELIEVE GENTLEMAN !

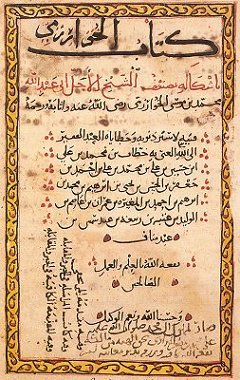

Using the old Roman numeral system made advanced math next to impossible. With a number system that goes from 0 to 9, al-Khawarizmi is able to develop fields such as algebra, which he initially used to calculate Muslim inheritance laws. He builds more on the geometry of the Greeks, and develops the basic ideas many high school math students can recognize today.

Using the old Roman numeral system made advanced math next to impossible. With a number system that goes from 0 to 9, al-Khawarizmi is able to develop fields such as algebra, which he initially used to calculate Muslim inheritance laws. He builds more on the geometry of the Greeks, and develops the basic ideas many high school math students can recognize today.